The 2020 presidential election will go down in history as one of Pennsylvania’s most memorable. The impact on Right-to-Know Law (RTKL) requests was swift, prolonged, and intense. Requesters sought records related to mail-in ballots, voting machines, and security policies. More than three years later, election related RTKL appeals still remain above pre-November 2020 levels.

With the 2024 Presidential election just eight months away, seeing where the dust has settled after this wave of requests and appeals helps give some insight into the current status of a number of important legal issues. A brief assessment of the relevant stats and data reveals a number of unresolved legal issues still exist regarding the public nature of election-related records. With the potential for Pennsylvania to be the focal point of yet another election, the impact of such uncertainty may intensify the stress on various agencies, the Office of Open Records (OOR) and the courts with a renewed resurgence of RTKL requests and appeals both leading up to and following the election.

Explosion in election appeals

From 2009 to 2019, approximately 35 Final Determinations issued by the OOR dealt with election related RTKL requests; from 2020 to the present, the figure jumped to 241.[1]

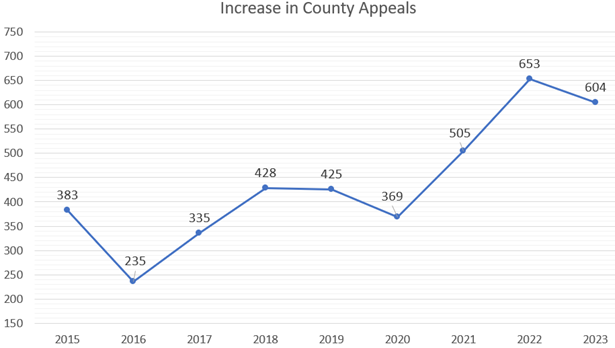

Since counties run elections, they were most impacted by the marked increase of RTKL requests. From January 2020 to January 2022, the OOR saw a 77% increase (369 to 653) in appeals of county records requests.[2] While the overall number declined between 2022 and 2023 (653 to 604), it is still a 64 percent increase as compared to before the 2020 election.

The increase in appeals tells a fraction of the story. A 2018 study found that less than three percent of RTKL requests are appealed.[3] Thus, the increase at the county level in RTKL requests is likely much more dramatic.

Various types of records requested

Commonly requested types of election records include:

- Cast Vote Records (CVR) which display a voter’s choice in each race, without their name attached. This was the most requested, and individual counties chose to respond in different ways.[4]

- Absentee or mail-in ballots or envelopes. The option of voting by mail without claiming absence debuted in 2020 in Pennsylvania, and several RTKL appeals dealt with requestors’ desire to access those ballots and envelopes. The name envelopes, which include a voter’s signature, and the ballots, which offer no identifying information, cannot be obtained in tandem.[5]

- Voting machine security and instructions records also garnered increased attention in the aftermath of the 2020 election.[6]

- Surveillance recordings. Some requesters requested video recordings of ballot drop boxes or poll workers counting ballots.[7]

- Election policies and procedures. Many requests centered around how elections are run from beginning to end.[8]

- Emails between public employees. A common focus for RTKL request for all issues, requesters wanted to see how election officials communicated about certain issues and what was discussed.[9]

Dozens of appeals in courts still pending

A much higher than average percentage of election-rated decisions made by the OOR were appealed to the Court of Common Pleas. On average, less than five percent of OOR decisions are appealed; among election-related appeals, that figure is closer to 14 percent.

The appeals to courts come from both requesters (43%) and agencies (57%); common issues at this level include those related to security footage,[10] mail-in ballots,[11] and cast vote records.[12]

Impact

What does all of this mean for the aftermath of the 2024 election?

First, a final, binding court decision on access to types of ballots remains outstanding. While the Commonwealth Court’s decision released last week upholds the privacy of Cast Vote Records,[13] it remains unclear what information is actually included in the CVR. This could still be interpreted as a big step to resolving the issue, absent an appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Some appeals remain pending, including those for records related to security footage and mail-in ballots, among others.

Second, another spike in requests and appeals will impact counties, agencies that oversee elections, as well as the OOR. It is important for those agencies to proactively prepare operationally and fiscally for the very real likelihood of another significant spike in requests and appeals and how they plan to navigate such an increase in the timeframe confines of the RTKL.

[1] Based on February 28, 2024 search of OOR’s database appeals with the words “election”, “ballot”, “voting”, or “vote”, in the description. Any final determinations not related to elections were removed.

[2] The OOR’s database of appeals does not provide an automated count of county appeals by particular issue. While this increase reflects all county appeals, including those not related to elections, it provides a representation of how a high-profile issue can lead to a spike in appeals.

[3] https://lbfc.legis.state.pa.us/Resources/Documents/Reports/610.pdf

[13] https://www.pacourts.us/assets/opinions/Commonwealth/out/57CD23_3-4-24.pdf?cb=1

The post states “The name envelopes, which include a voter’s signature, and the ballots, which offer no identifying information, cannot be obtained in tandem.[5]“ That is a mis-citation.

The cited case (2022-1975) ordered the production of envelopes, which were clearly public records.

The PA Election Code is clear that (dropping three key letters from the original quote; edit bolded) “The name envelopes, which include a voter’s signature, and the ballots, which offer no identifying information, can be obtained in tandem” as both are explicitly declared to be public records.

The County involved in that appeal has argued that (again bolding edits from the quote above) “When County elections administrators [argue that they] have chosen to violate the right to ballot secrecy found in the PA Constitution, the name envelopes, which include a voter’s signature, and the ballots, which bear a voter-identifying unique code also found on the envelopes, cannot be obtained in tandem, to limit public awareness and limit accountability so County may be free to repeat the same issue in a subsequent election” (which did happen, and could again, especially in the absence of clear public incentives or commitments to not repeat it). The Commonwealth Court is now considering arguments about that principle, though not quite on the points as described in this post.

This article overall suggests an OOR bias in favor of agencies. Misquoting a case for the opposite conclusion in support of keeping public records secret advances such a perception and damages faith in OOR neutrality (and/or competence in being able to interpret precedent).

LikeLike